Chinese Canadian History

The Early Chinese Canadians

(1858-1947)

The History: Looking at the Early Chinese in Canada

Chinese people had begun arriving in Canada before 1867, the year of Confederation. These early Chinese immigrants came from one tiny area of southern China and they spoke the dialects of that region.

Their experience differs greatly from those who have immigrated to Canada in more recent years. During the 1990s, for instance, the largest number of immigrants arriving in Canada came from China, but they came from every region of that vast country. As well, immigrants of Chinese descent arrived in the 1990s from Southeast Asia, India, South America and other places.

Many people look at early Chinese-Canadian history to study the anti-Chinese legislation that existed in this country until the Second World War. Awareness and understanding can help ensure that Canada does not repeat unjust actions of the past.

At the same time, the Chinese in Canada have a proud history here. They helped to build and develop our economy. As well, they formed communities to support and protect their fellow immigrants who arrived from China.

This exhibit explores the first century of Chinese-Canadian history, with the help of photographs, historical documents and suggested reading material from the collection of Library and Archives Canada.

Each section of this history is accompanied by a “vignette” -a comment from a fictional character created by Canadian author Paul Yee- suggesting what it might have felt like to be a Chinese immigrant in Canada in those early days. The fictional characters are based loosely on interviews with many members of the Chinese community in Canada.

Link to Original Article:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadiens-chinois/021022-1000-e.html

Why the Chinese Came to Canada

The year 1858 marked the start of ongoing Chinese immigration to the regions of British North America that would later form the present-day Canada. In the east were the colonies of New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia, as well as the “United Province of Canada,” including Quebec and Ontario. On the Pacific coast was the colony of Vancouver Island. At the time, none of these colonies had immigration restrictions. A vast area under the control of the Hudson’s Bay Company lay between these eastern and western settlements. First Nations people were the main residents in that area, as well as in British Columbia.

The first wave of Chinese immigrants to arrive in Canada were motivated by various push and pull factors. Negative factors can “push” people to leave their home while positive influences “pull” people towards a particular country.

The push factors, such as floods and wars in China, made it hard for people to grow crops for food, live in safety and peace, or make a living.

Pull factors for Canada were related to the young nation’s pace of growth. New settlements and new industries often had a shortage of workers. British Columbia’s distance from Europe and eastern North America meant that China was the closest large source of low-cost labour.

Decisions on where to migrate were also shaped by other factors, such as the efforts of labour recruiters, and influence of family and village networks.

From China: The “Push” Factors

Most Chinese immigrants to Canada in the last half of the 19th century came from one small area near the southern port of Guangzhou, in China’s Guangdong province. Of eight rural districts in that region, four had rich soil. In the other four districts, only 10 percent of the land was usable for growing food crops.

All eight districts were densely populated. Between 1780 and 1850, the population had jumped from 16 to 28 million people. Meanwhile, no new ways had been found to increase harvests in the region, so the land could not feed everyone.

The population growth led to a land shortage and higher rents for farmland. People without fields to grow crops had a hard time feeding themselves.

From time to time, farmers also faced natural disasters, such as floods and droughts.

The last half of the 19th century was also a difficult political time for China.

Poor living conditions led to a peasants’ revolt in 1851. The Taiping Rebellion, which ended in 1864, claimed 20 million lives across the country. Other peasant wars in southern China claimed 150,000 lives between 1854 and 1868.

During these unstable years, farmers were dragged into armies, crops were ruined and bandit gangs raided villages. The central Chinese government could not maintain law and order in the region.

For many years, European countries had been moving into China to sell their products. After losing the Opium Wars to Great Britain in 1842 and in 1860, China was forced to open more of its port cities to trade with Europe. When trade moved to these newly opened ports, less cargo passed through the port of Guangzhou. The result was that porters, warehouse hands and boat crews lost their jobs.

After the Opium Wars, a condition of China’s surrender was a massive payment to Great Britain, an amount which was one-third of the annual intake of China’s treasury. This cost was passed on to the ordinary Chinese citizens who had to pay higher taxes.

To Canada: The “Pull” Factors

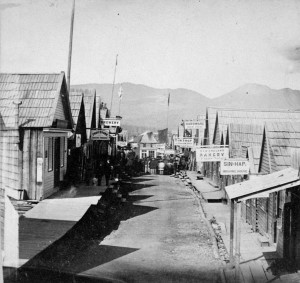

Gold was discovered along the Fraser River in British Columbia in 1858. Thousands of miners, including many Chinese who had been working in California, rushed into the region. Great Britain quickly created the colony of British Columbia on the mainland, with its capital city at New Westminster, to prevent American miners from claiming that the land belonged to the United States.

The need for labour in British Columbia led to many Chinese being hired to build roads, clear land and construct railways. They also worked in coal mines and fish canneries and on farms.

Working Overseas Not a New Experience

Guangzhou, on the delta of the Pearl River that pours into the South China Sea, was the main port in southern China. Since the eighth century, it had served merchants who traded far and wide with other regions of China, Southeast Asia and even the Middle East. Ships also carried workers from southern China to find jobs in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, as well as Guyana, South Africa, and Caribbean countries.

Long before North America’s gold rushes in the 1850s, men from the Guangdong region of China knew about overseas work. While they were away, the clan (a network of related families) helped their wives and children who had been left behind. The men working abroad were expected to send money back to their families and clans waiting at home.

Merchants from southern China working in faraway cities or countries would set up clubs to help fellow traders. These groups provided shelter, business contacts and small loans. Such services made it easier for the southern Chinese to travel far away.

When Chinese people came to Canada, they set up similar groups to help one another.

Link to Original Article:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadiens-chinois/021022-1100-e.html#a

Working in B.C.: Gold, Railway, Mining, and Salmon

In the 19th century, British Columbia earned its wealth from the export of resources such as gold, coal and salmon. Ships transported these goods to Europe and other parts of America. In the 20th century, British Columbia turned to the railway for moving goods. This time it was timber to build houses, and the destination was the Prairies.

The Gleam of Gold

In the Gold Rush of 1858, hundreds of Chinese miners joined 30,000 gold-seekers heading to British Columbia. In three years’ time, several thousand Chinese were prospecting there, and more arrived in the following years.

White miners had robbed, murdered and driven Chinese miners from goldfields in California. The Chinese feared similar violence in British Columbia so they did not compete directly with white miners. Instead, they reworked sites that white miners said were worthless. In these deserted claims, they found several dollars worth of gold each day.

The most gold was found in the Cariboo region, located 750 kilometres northeast of the site of the future city of Vancouver. It was there, in a town called Barkerville, that 3,000 to 5,000 Chinese lived. The Chinese trekked to all of British Columbia’s gold rushes and as far north as Yukon.

They also earned wages by working for various employers. They helped to build the Cariboo Wagon Road, a 614-kilometre route that took much-needed supplies into gold territory. They cut firewood, dug ditches, hauled gravel and built flumes (wooden channels for water) for the miners. They also grew vegetables and other crops because imported food was costly.

After the gold rushes ended around 1870, most people left the territory, but Chinese workers stayed to continue mining. In 1885, they made a big find near Lillooet and took out $7 million of gold.

The Railway: Connecting a Country

In 1871, British Columbia became Canada’s sixth province. A key point that persuaded the province to enter Confederation was Canada’s promise to build a railway to connect the Pacific coast to the rest of the country. One of the hardest parts of building the Canadian Pacific Railway was cutting through the Rocky Mountains.

Chinese workers were employed for several reasons. The most important reason was that, before the railroad was built, the easiest way to bring large numbers of labourers to British Columbia was by water across the Pacific or northwards from California. With the increasing demand for labour in British Columbia, Chinese labourers were indispensable. Chinese workers, however, were paid lower wages than white workers, even though they were more efficient. The use of Chinese workers has been estimated to have reduced the cost of building the railway by between $3 million and $5 million.

Among the Chinese crews were experienced workers who had helped to build railways in the United States. They cut out a path for the railway, tearing down trees and clearing undergrowth. They removed rubble from tunnels in the mountains and cut away hills. To build up roadbeds, they dug ditches for drainage on both sides of the path and then built mounds of crushed rock and gravel. The tracks and ties were laid on top of this path.

Railway construction lasted from 1880 to 1885. During this time, about 7,000 Chinese workers arrived in British Columbia, but they did not all stay for the entire job. At any single point of time, about 3,500 Chinese were on hand. They formed three-quarters of the total railway workforce in the province.

Many workers died from dynamite accidents, landslides, rockslides, cave-ins, cases of scurvy because of inadequate food, other maladies, fatigue, drowning and a lack of medical help. The death count of Chinese workers over the entire construction period has been estimated to be from 600 to 2,200 workers. No definite count exists because no one accepted responsibility for the Chinese workers beyond the work they did in laying the track.

The Mines: Underground Trouble

In 1900, 50 percent of Canada’s coal exports came from Vancouver Island. The coal mines depended on Chinese workers, but racism made the workers’ lives difficult. Thirty Chinese were first hired at a mine near Nanaimo in 1867. They sorted coal above ground. Then they went underground and pushed coal-filled tubs to the surface. White miners hired them as helpers to dig out coal. Soon the Chinese learned how to dig coal and formed one-third to one-half of all mine workers.

In 1877, white miners at Wellington, on Vancouver Island, went on strike for better wages and working conditions. The owner used Chinese workers to break the strike. White miners had not let Chinese men join their union.

In 1883, miners went on strike again at Wellington. Their union demanded that all Chinese miners be fired. The owner refused and the strike failed.

In 1887 and 1888, two terrible accidents, at Wellington and Nanaimo, killed a total of 208 miners, including 104 Chinese. White miners blamed the accidents on the Chinese miners because of their limited English skills. Investigators cleared the Chinese of blame but white miners succeeded in getting the provincial government to pass a law banning Chinese workers from working underground. Some mine owners, however, continued to use Chinese workers there.

In 1912, white miners started a strike on Vancouver Island that would last for two years. When one mine owner used Chinese strike-breakers, the strike-breakers’ homes and stores were looted.

The Canneries: Sharp Knives Needed

By 1900, salmon was British Columbia’s second most valuable export. The salmon-canning industry had grown with the help of low-cost Chinese labour.

It was a tough business to start. A lot of money was needed to pay for a site, buy salmon and supplies, and hire labour. The run of salmon might be low, which would reduce the supply of fish and raise its price. The selling price of canned salmon might drop if too much product reached the market. It took several months to ship the salmon to Britain and more time to sell it and receive payment. To make a profit, the processing costs had to be kept down. The use of Chinese workers made this possible.

Salmon canning was done by hand until machines took over in the 20th century. Cans were cut from sheet tinplate, formed and soldered by hand. When fish reached a cannery, butchers removed the heads and tails and gutted the fish. The fish were then cut up and stuffed into tins. The tins were cooked and then sealed.

White workers avoided this work because it was short term and unpleasant. Canning was done in July and August. Smaller crews worked in the few months surrounding the season.

In the 1870s, Chinese workers were paid between $25 and $30 per month while whites received between $30 and $40. The industry expanded and wages rose. In the 1890s, the discrepancy between the wages of white and Chinese workers was even greater.

Link to Original Article:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadiens-chinois/021022-1200-e.html

Working Across Canada: Laundries and Cafés

By 1901, Chinese people were living in every province of Canada, and in Newfoundland (which did not join Confederation until 1949). The highest number (15,000) lived in British Columbia. Prince Edward Island had only four Chinese people.

Across Canada, most Chinese did one of two jobs: washing laundry or working in cafés. Only in British Columbia did the Chinese work in many different parts of the economy.

Chinese Laundries: A Necessary Service

The first Chinese people in many Canadian cities were laundrymen. In Vancouver, the Wah Chong laundry started before the city came into being in 1886.

In an era before automatic washing machines, doing laundry was hard work. Water needed to be boiled, clothes hand-scrubbed and shirts starched in order to be ironed smooth. Anyone who could afford it would send out their laundry to be done. In cities, single men worked in factories, banks and offices. They lived in boarding houses or apartment hotels and they too needed their clothes washed.

Chinese-run laundries were found in cities, small towns and villages throughout the Prairies, Central Canada and the Maritimes. When Fong Choy opened a laundry in St. John’s in 1895, it was the first Chinese business in Newfoundland.

Chinese Laundries: Low Costs for Start-up

Laundries were a good way for a labourer to go into business for himself once he had paid off the debts he owed for getting to Canada. It did not cost much to start a laundry. All one required was a stove to heat water and dry the clothes, and a space large enough to hang laundry to dry in the winter. Of course, the laundryman also needed kettles, washtubs, scrubbing boards and soap.

White men left this job to the Chinese because it was viewed as women’s work. Moreover, it was not a popular job. Laundrymen worked long hours six and even seven days a week. They did not earn much because prices were low, due to competition from other washhouses. White men ran steam laundries that handled large orders of wash from hotels and hospitals. A lot of money was needed to start steam laundries.

Chinese immigrants started businesses such as laundries because they were forced out of many other professions by the increasing number of migrants who came from eastern Canada and Europe. Anti-Chinese organizers in British Columbia and California had argued that jobs in mining, logging, manufacturing, and other industries should be reserved for the white workers who were arriving in ever larger numbers on the railroads that the Chinese had helped build.

Chinese Cafés: Good Food at Good Prices

From the start of the 20th century, the Chinese opened cafés or restaurants in cities, towns and even small villages. They served western food such as roast beef, steaks, apple pie and ice cream. In many small towns and villages, the Chinese café owner would be the only Chinese living there. Often he opened his restaurant close to the railway station or the horse stables, places where he found customers. Later, after the Second World War, these restaurants introduced people to Chinese food.

Chinese Cafés: Popular Hangouts

Chinese-run cafés started in western Canada for the same reason as Chinese-run laundries. A Chinese labourer could borrow start-up money and learn the business from relatives who had already opened laundries or cafés. After many years building up a business, the operator of a laundry or a café could in turn sell it to a younger man just starting out, often lending them money to get established.

The first half of the 20th century saw growth in the economy and the population. More and more railway lines were being laid. Immigrants came to break the soil and start farms. Stores and shops sprang up at central points to provide settlers with goods and services.

Chinese immigrants also found work as domestic staff. Although the men are not identified in this photo, possibly taken in Lunenburg, N.S., they may have worked for a household there. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

In the Prairies, many cafés rented out rooms to travellers or sold groceries to the townspeople. Farmers living far away brought their families to town to do errands. To them, a meal at a Chinese-run café was a special treat. They could chat with townspeople, because shopkeepers and shoppers dropped into the café for coffee and pie, or a meal. From the 1920s on, Chinese-run cafés became a popular hangout for young people.

In cities, Chinese-run cafés were found in the downtown core, where their customers were office workers, department store clerks, shoppers and travellers. Because many cafés competed for business, the prices were very reasonable. Low prices also attracted people who were jobless or otherwise down on their luck.

In some places, the Chinese-run café became very famous. In London, Ontario, Lem Wong brought in a big-band orchestra and ran supper dances. His restaurant had tablecloths and his waiters were trained in New York City. Customers came from the best families of the city and dressed up for the occasion.

Running a café was hard work. The hours were long, from dawn until midnight. Some towns did not have running water. Sometimes customers behaved badly: throwing dishes and furniture around. And, as in all small businesses, sometimes customers left without paying.

Link to Original Article:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadiens-chinois/021022-1300-e.html

Racism in Law and Society

Federal Laws

A cartoon from the Canadian Illustrated News, 1879, entitled The Heathen Chinee in British Columbia. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

As soon as the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway was completed in 1885, Canada took steps to stop Chinese immigration. The Canadian government acted because it, and not any province, had power to make laws related to immigration. The pressure to pass such a law came from British Columbia, but Ottawa took action only after the railway was finished.

Under the Chinese Immigration Act (1885), the Canadian government forced every Chinese worker, and family member, wanting to enter Canada to pay a $50 head tax. (In 2008, this amount would buy goods worth $1,100). It was assumed that Chinese people were too poor to pay and therefore would not be able to come to Canada. Merchants and students were exempt from the tax. No immigrants from any other country ever had to pay such a tax to enter Canada.

Government officials kept track of each person who paid, or was exempted from, the tax in large books called the General Registers of Chinese Immigration. These records were maintained from 1885 to 1949 and can now be searched online through the LAC database,Immigrants from China.

The tax worked for a while. The number of Chinese newcomers dropped from 8,000 in 1882 to 124 in 1887. However, more Chinese started coming in the next decade, and Ottawa raised the head tax to $500 in 1903. This amounted to more than a year’s wages for the average worker.

The new tax reduced Chinese immigration for a few years. The number of Chinese newcomers began rising again in 1908. In British Columbia, anti-Chinese feelings grew stronger. After the First World War, the economy slowed down, and jobs were hard to find. Many whites blamed the Chinese for taking work away from white people.

In 1923, Canada passed another Chinese Immigration Act, which stopped Chinese immigration. Chinese people living here had to register with the government or they could be deported. They were allowed to go home to China for visits and then to re-enter Canada. But no new immigrants could come in. This meant that Chinese men living here could not bring their families into the country.

Provincial and Local Laws

Community leaders sought better treatment under the law. Shown here is a letter and newspaper article concerning the labour law preventing white women from working in Chinese-run establishments. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

After joining Confederation in 1871, British Columbia demanded that no Chinese workers be used to build the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Canadian government would not agree.

The British Columbia legislature passed laws against the Chinese. They could not vote or be hired on public works projects such as road-building. When the Chinese were first banned from voting in 1872, they formed the majority of voters in some electoral districts. Cities such as Vancouver and Victoria also had rules against using taxpayers’ money to hire Chinese workers.

Saskatchewan was the other province that did not allow Chinese to vote in its elections. The voters’ list for federal elections took names from provincial voters’ lists, so this meant Chinese residents of British Columbia and Saskatchewan could not vote for Members of Parliament.

Why So Hostile?

Anti-Chinese agitation became a powerful force in British Columbia politics. Blaming Chinese immigrants when the economy turned bad became a way of organizing migrants from Great Britain and Europe around the idea of “white supremacy,” captured best in the phrase “White Canada Forever.”

Chinese Canadians who served in the Canadian military during the Second World War helped pave the way for the 1947 repeal of the Chinese Immigration Act. This legislation had banned almost all immigration to Canada from China since 1923.

Shown here in 1947 (front row, left to right): Lance-Corporal C. Lum, Corporal R.W.J. Lee, Company Sergeant-Major D. Sung, Sergeants C. Hoy and M. Chiu. (Rear row, left to right): Lance-Corporal D. Yo, Corporal Y.M. Wong, Corporal C.P. Wong, Sergeant H.B.D. Lee, Lance-Corporal R.W. Yeastings. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

Anti-Chinese agitators saw that Chinese immigrants came here without families and lived simply. Therefore, they said, Chinese men did not need as much money as whites did to live on and to raise a family. They argued that the Chinese could work for lower wages and would take jobs away from white workers.

White British Columbians also firmly believed that their way of life was better than all others. They saw China as a weak nation of backward people who could never learn to live like white Canadians. Moreover, they said that Chinese people carried diseases and other bad habits (such as smoking opium) that threatened Canada’s well-being. Racism against Chinese and other immigrant groups such as Japanese and South Asians, as well as against First Nations peoples, were expressions of a powerful belief in white superiority.

In part, anti-Chinese racism reflected a belief in the superior power of the British Empire, as the strongest political and military force in the world during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The majority of British Columbia’s white population had ethnic origins in the British Isles. Between 1911 and 1941, they formed 70 percent of the province’s people, while immigrants from other European countries formed 16 percent. British Columbia’s white immigrants also came from the United States and other parts of the British Empire where anti-Chinese racism existed.

Municipal and provincial governments in British Columbia passed the largest number of anti-Chinese laws, but anti-Chinese racism existed across Canada. In 1910, Calgary property owners living near the city’s Chinatown wanted to block its growth because of fears of falling real estate prices. In the 1910s, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario prohibited Chinese employers from hiring white females, out of fear that they would take sexual advantage of the women. In 1915, white laundry owners in Montréal called for citizens to boycott Chinese laundries.

Intolerance Becomes Harassment

In daily life, white Canadians felt free to show their dislike of Chinese people without any concern for the consequences.

A feature of many Chinatowns was the “Joss House”, a hall with altars of gods and clan ancestors where immigrants could pay their respects. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

Children tormented Chinese peddlers on the street, tipping their carts and destroying what they had to sell, while politicians and newspaper editors condemned the Chinese in speeches and writings. Sometimes public swimming pools were off-limits to Chinese people. As well, Chinese people were only allowed to sit in special sections of some movie theatres.

In 1907, a mob of several thousand white men and boys crashed through Vancouver’s Chinatown, breaking every single window there. Japanese neighbourhoods were also vandalized. People in Chinatown feared a bloody massacre and hurried to buy guns to defend themselves. The Chinese and Japanese communities organized a protest to demand that the federal government pay for the damages. The government held two Royal Commissions, led by William Lyon Mackenzie King, which resulted in payment for their losses.

In 1919, several hundred soldiers and civilians rampaged through downtown Halifax. They swept into six Chinese-run cafés to break furniture, loot cash registers and steal goods.

In 1922, school trustees in Victoria, British Columbia, tried to take Chinese students out of regular classes and put them in a separate school. The Chinese community protested fiercely by taking their children out of the schools for an entire year.

During the Depression in the 1930s, Chinese Canadians did not receive the same amount of assistance that was given to white people. In Vancouver’s Chinatown, the provincial government gave the Anglican Church 16 cents a day per person to set up a soup kitchen while in other areas white people in need received meal tickets worth 15 to 25 cents each. In Alberta, relief payments of $1.12 per week were given to Chinese people, less than half the amount provided to others.

Individual acts of kindness did occur. For example, newspapers on occasion published letters to the editor that decried bullying of the Chinese. Missionaries in Canada had also befriended the Chinese immigrants since the turn of the century. In the final analysis, though, these sympathetic gestures were greatly outweighed by both the institutional and everyday hostility encountered by the Chinese. The situation only started to improve after the Second World War.

War Brings Changes

More professional opportunities opened to Chinese Canadians after the Second World War. Vancouver pharmacist Lim D. Lee is shown in this 1951 photograph. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

During the Second World War, China and the Allies fought against Germany, Italy and Japan. Chinese Canadians joined Canada’s armed services. On the home front, Chinese Canadians from all walks of life raised money in public campaigns for Canada’s war effort. They also donated funds to support China’s fight against Japan, whose army had invaded their homeland.

The horrors of Nazi racism and the genocide of Jews and other victims of the Holocaust forced white Canadians to confront their own views on race. Earlier, newspapers and labour unions had portrayed the Chinese as unwelcome aliens. After the Second World War, newspapers and labour unions joined church leaders in demanding that the Canadian government treat its Chinese citizens as equals.

In 1945, Canada helped establish the United Nations, which declared equal rights for men and women, and called for people to live together in peace as good neighbours. As part of this commitment, the Canadian government was obliged to review its anti-Chinese laws.

In 1947, it repealed the 1923 law that had stopped Chinese from immigrating to Canada. Chinese Canadians soon had the right to vote all across Canada and for all levels of government.

But the government retained other policies that were unfair. The federal government did not treat Chinese Canadians equally on immigration. Chinese Canadians could bring in only a few family members, while other Canadians could sponsor a much wider range of relatives. In 1967, Canada finally removed restrictions on the basis of race, ethnicity and national origin to its immigration regulations and implemented a “point system.”

Link to Original Article:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadiens-chinois/021022-1400-e.html

Communities for Canada and China

Chinatowns Across Canada

All across Canada, starting in the 1890s, cities and larger towns began to develop their own Chinatown districts. These areas were safe places for Chinese people to live, to find Chinese goods, and to meet socially. People who wanted to harass the Chinese would be less likely to do so when many Chinese people lived and worked close by and could fight back. Chinatowns often emerged in older, poorer parts of town which were less desirable.

Some of the few white people who visited Chinatown regularly were Christian missionaries. They taught English, preached the gospel and tried to make the Chinese into Christians. They found the most success with Canadian-born Chinese.

Chinatowns also contained halls with altars featuring various gods and/or clan ancestors. Immigrant men paid their respects there.

Before 1923, most of the Chinese people living in Canada were men without families. They were unmarried, or had wives and children waiting in China. The men sent money home regularly and made plans to return to China to retire. People who had enough money also brought their families to Canada to settle. But after 1923, Canada shut its door to Chinese immigrants.

Looking Toward China

Children were always a welcome sight in Chinatown. Few Chinese families lived in Canada until the immigration laws were changed after the Second World War. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

From the 1890s onward, Chinatown provided news about the homeland, which Chinese immigrants keenly followed. China wanted to modernize its industries, education system, and army and navy. Its government changed from a monarchy to a republic. These were exciting issues.

Chinatown provided goods and services needed by the immigrants. Its stores sent money on behalf of immigrants across the Pacific to their families in China’s villages. Grocers imported familiar Chinese foods. The immigrants visited barbers, restaurants and herb doctors. In larger cities, Chinese firms published newspapers, prepared time-honoured barbecues and baked traditional cakes. Although many Chinese lived and worked outside of Chinatowns, the districts served as hubs for activity and central gathering places for men who were spread far and wide across Canada.

Mutual-help groups in Chinatown rented out rooms and provided space where men met, discussed politics and gambled. They organized banquets for the Lunar New Year or graveyard visits on Ancestor Day. They raised money for causes in China, such as flood or drought relief. When Japan bombed Shanghai in 1932 and sent its army to invade China in earnest in 1937, the Chinese in Canada raised money to defend their homeland.

Looking Toward Canada

A gathering in Toronto‘s High Park in 1919. As a generation of Chinese Canadians born and raised in Canada developed, many organizations formed that paralleled mainstream society. Although still segregated by racism, Chinese Canadian sports teams, Boy Scouts, and beauty pageants reflected the desire of Canadian-born Chinese to live similar lives to other Canadians. (http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca)

The Chinese Benevolent Association in cities across Canada spoke for the community. After 1923, it held protests called the “Day of Humiliation” every July 1, the day that the law banning Chinese immigration came into effect. During the Depression, the association asked the government for help for Chinese communities.

Before 1923, the small number of Chinese who had families in Canada were mostly merchants. The head tax had made it costly for Chinese Canadians to bring relatives to Canada. The merchant families included Canadian-born Chinese, who grew up speaking both English and Chinese. They formed sports teams in soccer, hockey and basketball, and played teams from outside the Chinese community. Some attended university. However, anti-Chinese racism stopped them from finding good jobs in Canada.

When the Communists took power in China in 1949, many Chinese in Canada decided not to return to China. Instead, they brought their families to Canada. With growing public acceptance of the Chinese here, Chinese Canadians faced a brighter future.

British Columbia was home to over 60 percent of Canada’s Chinese before the Second World War. But for many years after the ban on Chinese immigration was revoked in 1947, the province received only one-third of new Chinese immigrants. This meant that Chinese families were settling all across Canada.

Link to Original Article:

http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/canadiens-chinois/021022-1500-e.html